From Pilot to Powerhouse: The Evolution of China’s Carbon Emissions Trading System

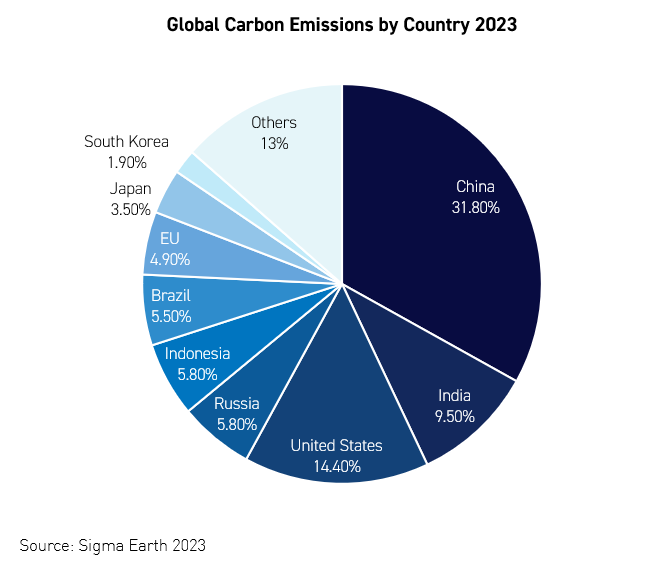

As a signee of the Paris Agreement, China has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 and peak its carbon emissions before 2030. According to the World Resource Institute, China is currently the largest greenhouse gas emitter. As such, the need to reduce its emissions is urgent from not only a public health and environmental perspective, but also a financial one.

As part of this transition, China utilized many innovative economic tools and became the largest investor and manufacturer of renewable energy. Currently, China is leading the world in the production of solar photovoltaics, lithium batteries, and electric vehicles. In addition to these manufacturing efforts, China is also trying to implement financial controls to curb emissions from its heavy polluters and incentivize companies to choose sustainable sources of energy. For example, in 2021, China introduced its national Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Although China’s ETS is still in its early stages, it is already the largest in the world in terms of covered emissions. At the moment, it only contains the power sector (electricity and heat), which emits a staggering 5 Gt of CO2 annually (15% of global emissions) (ICAP 2024)2. However, in the last four years, China’s ETS has not been operating efficiently to reduce emissions. This is because in comparison to its European and American counterparts, the Chinese ETS’ permit allowances are too generous and cheap for companies to purchase, while penalties are low. Fines for failing to comply is a one-time fee of 2,822-4234 USD in China while in EU, companies that fail to surrender are charged 100 Euros per tonne of CO2 and are still liable for the required allowances.

Although the national ETS currently only covers the power industry, China plans to expand its carbon market to cover petroleum refining, chemicals, non-ferrous metal processing, building materials, iron and steel, pulp and paper, and aviation. In September 2024, China announced that it plans to include cement, steel, and aluminum production in its ETS by the end of the year.

China’s ETS does not set a cap on total emissions. As such, the current use of the carbon market in China is mostly for data collection and planning purposes. It is not market-driven enough to produce efficient results in the economy or the environment. Whereas other ETS set an absolute cap for emissions, China's ETS is intensity-based and factors economic growth and quantity of emissions simultaneously when determining the cap. As a result, the cap is set based on a projected GDP, but may be adjusted based on the result to allow more flexibility. In other words, if there is exponential growth in the economy, the overall emission could still increase with this model.

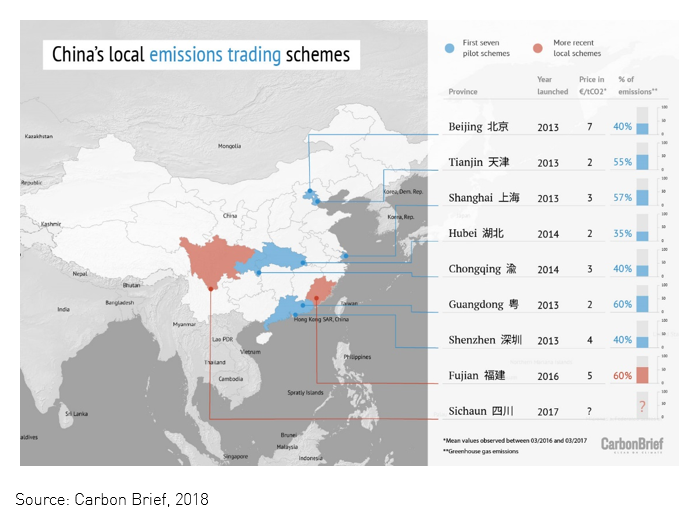

As a precursor to the national ETS, China launched a series of pilot ETS programs beginning in 2013. These pilot programs are located in different cities across the country including: Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Hubei, and Guangdong. They are meant to test different allocation methods and develop local capacity before scaling up to the national level. For example, the Shenzhen ETS was the first to operate in China. This ETS covers around 50% of the city's emissions and uses free allocation. In other words, allowances have been allocated freely using both benchmarking and grandparenting. Shenzhen's market has the highest liquidity in all of the pilot programs, and is regulated by a dedicated ETS bill passed by the municipal legislator instead of subnational governments. Eventually, the plan is to take lessons learned from different models of pilot programs and incorporate them into the national ETS.

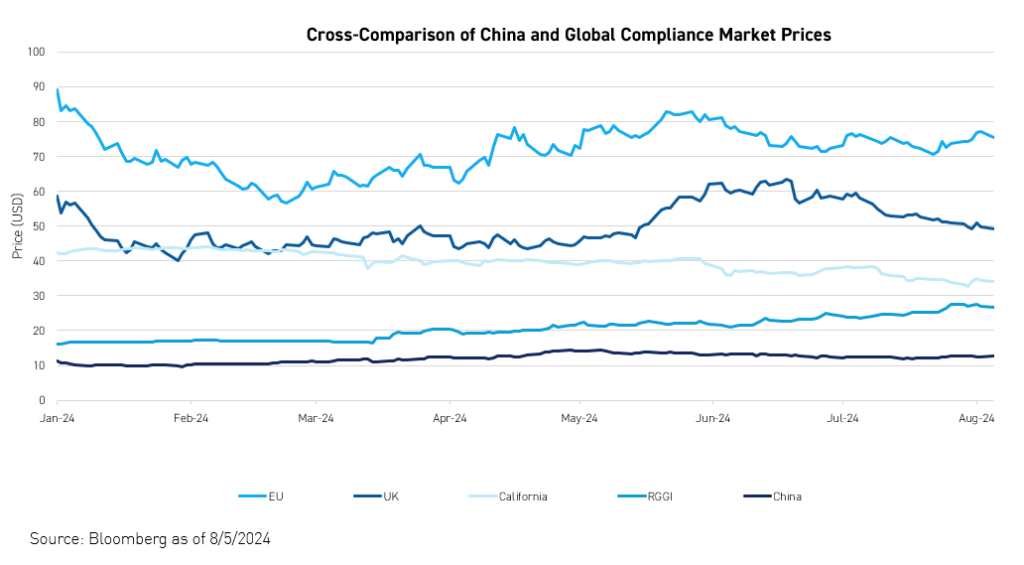

Different carbon markets have different approaches to regulating prices and emissions. The EU ETS has used 100% auctioning since 2013, whereas California uses consignment auctions for certain industries and 100% auctioning for others. The consignment auction combines free allocation and the auction. It is useful for early stages ETS because it reduces the volatilities of the commodity market that is brought on by ETS. The Northeast power market (RGGI) also auctions more than 90% of its carbon credits. This means that each system, by design, has different price or supply adjustment measures. KraneShares Global Carbon Strategy ETF (ticker: KRBN)encapsulates the top 4 carbon allowance markets, including: EU, California, RGGI, and UK.

In China, to create a market-driven approach to carbon pricing, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment has expressed its desire to eventually roll out the auction process in its ETS. There is massive potential in auctioning carbon credits. Even if only 2% of all carbon credits are auctioned in China at $10 per ton, the revenue would be $900 million per year. For comparison, the EU ETS averages around 68.73 Euros per ton of CO2. In 2023, EU auction revenue was at 47.4 billion US dollars. Auctioning will greatly increase market liquidity and moderate price volatility. These are funds that can be redirected to R&D and other climate mitigation investments.

With KraneShares’ longstanding history of investing in China, we are closely watching developments in China’s carbon market. Our flagship KraneShare Global Carbon Strategy ETF (Ticker: KRBN) is designed to include new markets as they come online and meet necessary liquidity thresholds for index inclusion. Currently, emission trading systems across the globe cover about 24% of total global emissions (World Bank, 2024)5. Although at the moment, there is no futures contract available for China's ETS, we expect to see China's carbon allowances added to KRBN's index once futures contracts are introduced and meet the liquidity requirements.

For KRBN standard performance, top 10 holdings, risks, and other fund information, please click here.

Citations:

- Data from Sigma Earth 03/01/2024

- Data from ICAP 2024

- Data from Carbon Brief 2018

- Data from Bloomberg 08/05/2024

- Data from World Bank 2024